Healing the Planet: Hospitals Take Steps to Go Green and Reduce Emissions

Summary

In the United States, healthcare is responsible for 8.5% of greenhouse gas emissions, a major contributor to climate change, and the problem is growing worse.

Climate change leads to extreme weather events that take a huge toll on patient health, from complications and even death due to excessive heat, to air pollution that leads to worsening respiratory and cardiovascular conditions.

Some hospital systems like Gundersen Health based in LaCrosse and UW Health in Madison are tackling the problem with innovative solutions.

Gundersen Health became the first system to achieve energy independence in 2014 through a combination of strategies, including reducing energy usage by turning off their HVAC systems when not in use and generating power through renewable energy sources like wind, solar and biomass burning innovations.

UW Health has focused on reducing energy usage and waste streams. Healthcare is responsible for 5 million tons of waste each year.

To tackle the problems of wish-cycling and excessive waste, UW Health is focused on building a culture of sustainability. They involve nursing staff at the ground level, then leverage their dedication and passion for patient care to champion the operational changes necessary to move the needle on waste. As a result, they cleaned up their recycling even during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Both systems - Gundersen Healthcare and UW Health are models for an approach to sustainability, but warn that it takes a serious commitment of resources and time, and hospital leadership has to drive the effort from the top. It also takes considerable ongoing effort to avoid “efficiency erosion.”

The reward for hospitals that get serious about implementing sustainability measures is better staff engagement, and potentially a bump in recruitment activity. Physicians want to work for a system that reflects their values.

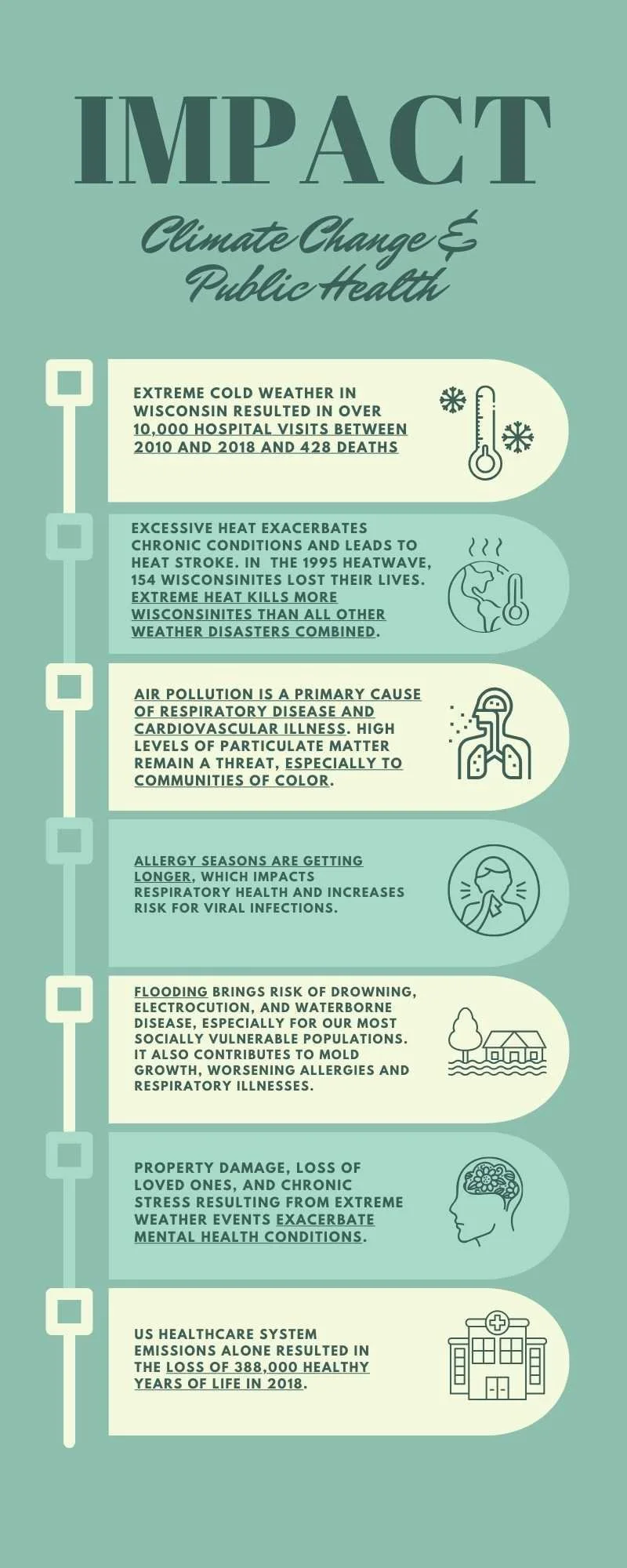

Climate change impacts health on many dimensions.

Hospitals should be a place of healing and wellness; however, a much darker side of healthcare is threatening the physical and mental wellbeing of patients. Modern health care systems are major contributors to the already significant burden of climate change.

In the United States alone, healthcare is responsible for 8.5% of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) due to energy-intensive operations, large facilities, and excessive medical waste. Sadly, the problem is getting worse; between 2010 and 2018, healthcare GHG emissions grew by 6%.

The health impacts of climate change are well-documented (see side bar)

“Impact: Climate Change & Public Health” source links can be found at the end of the article.

Organizations like the Wisconsin Environmental Health Network and Healthy Climate Wisconsin believe the industry has a moral obligation to track and measure efforts to improve sustainability and its impact on public health, yet only 12% of healthcare systems published a sustainability report in 2015 or 2016.

In Wisconsin, some systems are working to turn the tide, and applying their hippocratic oath to “do no harm.”

Gundersen Healthcare takes the lead

Alan Eber’s path to Envision—Gundersen’s environmental health program, was unusual if not inevitable. As an engineer, he began his career designing HVAC systems for a train company in LaCrosse (trains emit the lowest GHGs in the transportation sector at 2%) for 13 years.

When Eber arrived at Gundersen seeking a change, he started out in construction management and eventually became a project manager on their renewable energy projects.

In 2008, Gundersen planned to double the size of their campus with a new addition to the hospital. CEO at the time, Dr. Jeff Thompson, who was instrumental in the adoption of the system’s sustainable approach to building, energy, and waste management–a program they called “Envision,” walked in the door and asked Eber and his team of engineers, “Do you think we can achieve an expansion with net-zero energy?”

After researching what it would take, Eber and his team realized it wouldn’t be very difficult. In fact, they learned they could make the whole system energy independent, not just the addition.

Dr. Thompson gave the go-ahead and kicked off Gundersen’s 6-year journey to energy independence.

Eber attributes their success to three major strategies:

They use less energy. A lot less. Their usage dropped 30% in two years, “just by being more thoughtful and aware of how we were using our energy,” said Eber. An easy win was turning off the HVAC systems when they weren’t in use. He explained that HVAC systems normally represent the largest share of energy use in any hospital system.

They generate power. “We can’t conserve our way to net zero energy,” says Eber. So they used Wisconsin’s rich natural resources to generate clean power, including:

Two 5-megawatt windmill sites in Lewiston, Minnesota and Cashton, Wisconsin.

Solar arrays on every campus. One recent example is the 388 solar panels on the roof of its Behavioral Health building, which generates more than enough energy to power the building. The excess power is used in the system’s on-site power plant. Gundersen is now the largest private owner of solar panels in Wisconsin.

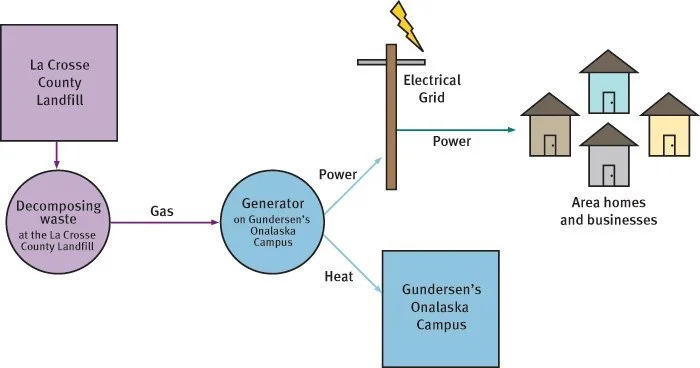

Garbage from landfills. Municipal solid waste landfills are the third-largest source of methane emissions in the United States, so Gundersen partnered with the local landfill to capture the methane generated and now they use it to produce electricity and heat for their campus. “We are heating our buildings for free until the temperatures dip to around 30 degrees,” after which they need an energy assist from utilities.

3. They use a boiler system. Using a biomass boiler system, they burn wood chips that are organic and free of paint, glue or other toxic treatments. When the sustainability team at Gundersen measured energy usage, they learned heat was their biggest culprit. Now, instead of relying on natural gas they use this unique boiler system to burn locally sourced wood fuel sources–milling and foresting scrap–and use the resulting steam energy to heat their entire LaCrosse medical campus—over 1 million square feet of facility space. This system saves Gundersen about $500,000 per year.

Burning wood chips creates steam energy that heats Gundersen’s LaCrosse medical campus, generating $500,000 savings per year.

Employing these strategies, Gundersen achieved energy independence in 2014 and became a clear leader in hospital sustainability. And they have no intention to rest. “We can’t stop moving forward, or we’ll move backward,” says Eber. “We call it efficiency erosion. If you do nothing, your buildings get worse year after year.”

Their plans for the future include some audacious goals:

They aim to use 50% less energy in their buildings than a typical healthcare system. They are currently running at 42-43%, and project reaching their goal by 2026.

They are building a resilient campus at their Onalaska site in partnership with their local utility. The four buildings on that campus will be put on an all-renewable microgrid. This means that in the event of a power outage, they have back-up power sources to ensure continuity of care for their patients. A battery and the local utility will serve as a backup power source.

One might ask how one system can achieve so much. While Ebert and the team at Gundersen health have worked out a simple solution to address the energy demands of a healthcare system, the challenges of implementation lie with the willingness of the staff.

In an organization with tens of thousands of employees and other stakeholders, many of whom are overworked and stressed out due to a global pandemic and staff shortages, major shifts in the way things are done could push some staff to a breaking point.

But Eber reports increased engagement. “There’s a pride factor in working for our healthcare organization,” he said. He also heard anecdotal reports of bumps in recruitment efforts. “Physicians would come to Gundersen to interview because they heard about our sustainability initiatives. They want to work for an organization with those values.”

No system makes those kinds of changes without forethought and planning. The next system example provides some clues about how to bring staff along on the sustainability journey.

UW Health Focuses on Building a Culture of Sustainability

Tom Thompson — Dr. Jeff Thompson’s brother, took an indirect path to healthcare sustainability work. He studied wildlife ecology and began his career as a zookeeper. Eventually, he shifted his focus from animals to people, and landed at Gundersen Health System, where he was part of the team that supported their path to energy independence. After a leadership change, Tom moved on and accepted a position with UW-Health as their Sustainability Coordinator.

Like Gundersen, UW Health—under Energy Management and Sustainability Program Manager Mary Evers Statz’s leadership, is focused on energy efficiency. They’re working toward turning off light and HVAC systems when not in use, improving building insulation, and incorporating renewable energy sources like solar into their building plans.

They are also involved in groups that apply pressure strategically to vendors, government actors, and other hospital systems. Examples include:

Practice Greenhealth, a cousin of Healthcare without Harm. Thompson says these organizations help them rally people and organizations to “drive change upstream.”

Group Purchasing Organizations (GPO). Under these structures, large health systems combine forces to get better pricing, but they also leverage that purchasing power to demand more sustainable products, such as those without PCBs, which are harmful to patients.

The nationwide Better Climate Challenge. UW Health was one of the first health systems in the country to join the challenge, committing to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% within 10 years.

Thompson’s particular focus is on waste streams—recycling, hazardous waste, infectious waste, and regulated medical waste. In the US alone, hospitals generate a staggering 5 million tons of waste each year, so there’s a lot of work to do.

Receiving an aware from Practice Greenhealth. Pictured (left to right): Tom Thompson, UW Health Sustainability Specialist; Dr. Karin Zuegge, Anesthesiology, Medical Director for Sustainability, UW Health OR Green Team Champion; Mary Evers Statz, UW Health Program Director, Energy Management and Sustainability; and Dr. Meghan Warren, Associate Medical Director at Transformations Surgery Center and member of the UW Health OR Green Team.

Improper disposal of medical waste in landfills leads to contamination of drinking water, surface water and groundwater, and many other downstream health risks.

“If I can prevent pharma waste from entering our waterways, that’s helping our drinking water and groundwater for a long time. The work we do is immediate and very urgent, but we also need to think further down the road,” says Thompson.

His strategy for success? Start with the frontline staff, nurses in particular, to build support and buy-in for changes.

Nurses take the lead on sustainability at UW Health

“In healthcare, if you really want to get anything done in sustainability, you need to involve nursing,” says Thompson. “The people who can shut down an initiative or be your best allies are nurses, because they touch everything.”

He also insists that nurses are the most skilled at balancing their care and compassion for their patients with evidence-based care. “If you show them why something is important, they will rally behind it and become champions.”

For example, Thompson wanted to tamp down on “wish-cycling,” the practice of tossing something in the recycling bin, hoping or assuming it’s recyclable. The practice was widespread, and ended up contaminating recycling streams, putting workers further down the chain at risk.

“A lot of single use medical devices are plastic and they have a symbol on them,” says Thompson. “But just because it has a symbol doesn’t mean it’s recyclable.”

So he joined forces with nurse educators to focus on properly sorting waste.

When he examined the problem on site, he discovered the waste receptacles were placed ten steps away from where the nurses were treating patients. Ten steps doesn’t seem like a lot, but multiply that by 100 patients per day, and it adds up. “So we made it easier by moving the buckets closer to where they were doing their work” says Thompson.

Prior to our efforts, the hospital’s recycling was totally rejected for over a year due to severe contamination. After he worked with nurse educators, nursing staff on the units , environmental services, and the organization’s waste committee they were able to clean up the recycling and reduced the total quantity of hazardous waste during the height of the pandemic – a time when hospital staff were stressed out, scared, risking their lives, and being pushed to their absolute limit.

He explained that getting on the floor, and showing them what to do rather than sending “thou-must” emails is how they succeeded. “Once you create that culture of sustainability and nourish it, it’s like a good infection,” said Thompson.

“The thing that I have found, and I talk about this all the time, is that we are in the people business. You can generate all kinds of charts, graphs, and datasets, but the truth is if you go talk to someone, and say, ‘your work matters,’ show them a personal touch, and a willingness to join them on the front lines,” they will respond. “You gain street cred by being with the people and getting your hands dirty.”

Thompson insists that an important step in building a culture of sustainability is to celebrate. “Come back when there’s an impact and tell them, celebrate them. ‘You’ve saved a hundred pounds of waste from going into the landfill.’”

Another example was the energy consumption in Operating Rooms, which sees peak usage between 7am and 6pm. Slowing down or turning off the HVAC system results in dramatic decreases in energy usage. “If you tell nurses why, then they are the advocates. They will come to us and report results. By having an engaged and empowered staff—people who see us as allies—we’re not here telling them what to do, but how they can make it work with their workflow,” says Thompson.

“My job is to make sure this continues if I’m not here. I’m here to teach people so the culture can sustain. I do this for the greater good.”

Building Awareness, Sharing Wins, Inciting Change

Both UW-Health and Gundersen see sharing their successes and lessons learned as a critical part of their sustainability missions.

Find source links at the end of the article.

At UW-Health, they leverage their role as a teaching institution to partner with the UW Madison nursing school. They make presentations to the advanced nursing classes, show them what to look for and questions to ask to gauge a system’s sustainability, wherever they might decide to build their careers.

They also collect and share data in academic papers and at national healthcare industry conferences. They have a lot of wins to share (see sidebar), but Thompson says sharing failures is just as important.

“If something doesn’t work, we share it. We figure out why it doesn’t work and say ‘Here’s what not to do.’ He said people are more willing to listen to the wins when they know you’ve taken some knocks along the way.

At Gundersen Envision, after a few years of taking calls from other systems asking for advice about implementing sustainability programs, it was eating into hospital resources, so they officially started consulting and charging a fee for the services they provided. “For the past 4 months we have been developing what a real energy service organization looks like.”

They are now offering services to hospital systems that want to explore energy efficiency improvements, renewable energy projects, and more.

First step: Commit

Increasingly, hospital staff and leadership are buying into the need for urgent action on sustainability. Even The Joint Commission - the nation’s largest accrediting institution for hospitals - is in the early stages of setting standards for environmental sustainability for hospitals seeking accreditation.

But getting serious about sustainability comes with a cost. Eber’s advice to physicians and hospital administrators is to understand why you’re embarking on a sustainability program. “You really need to tie it to your mission. We’ve seen so many organizations hire a sustainability manager and say, ‘go do some stuff,’ says Eber, “but at the end of the day, the leadership says, ‘we can’t give you the resources.’”

Eber stresses that organizations that are serious about sustainability need to crystallize their “why,” and then carve out the resources they will need to achieve results.

His second piece of advice is to stop waste. “I could spend a lifetime trying to reduce waste in health care.”

Patients have power, too. Everyone is impacted by climate change, and both Eber and Thompson stress that patients can use their voices to help secure a more sustainable future in healthcare.

Thompson discusses the Indigenous philosophy of Seventh Generation Stewardship, a call to people living today to make decisions that result in a sustainable planet seven generations into the future. Every person can practice this stewardship by using their voice to draw attention to issues like the growing GHG emissions from the medical community.

On a related note, Eber stresses that one of the reasons hospitals are lagging other industries in sustainability efforts is that their customers aren’t demanding it. It’s understandable. If you’re driving your kid to the ER with a broken arm, you’re not thinking about which hospital is using renewable energy.

But when we use the hospital system for routine or preventative care, we can and should talk with our providers about the climate impact of their decisions. Tell them it matters.

Ebers stressed that policymakers also need to hear the message about the need for energy conservation in the healthcare industry, and to make sure that government incentives, such as those in the Inflation Reduction Act, are designed to encourage investments in sustainability.

The work people like Ebers and Thompson are doing is urgent, but they can’t do it alone. “It’s a big responsibility for all of us,” says Thompson. “Not just nurses and docs.”

UW Hospital employees used their break time to help create this picture of the famous Union Terrace chairs using the colorful plastic caps from medical vials that would have gone into the trash if not used for the project.

Source Links

Sidebar: “Impact: Climate Change & Public Health”

Extreme Cold in Wisconsin - Trends, Surveillance, and Prevention

Climate Wisconsin Stories from a State of Change: Extreme Heat

USDA: Yes, Allergy Seasons Are Getting Worse. Blame Climate Change.

Connecting the Dots on Flood Risk, Climate Change, and Public Health.

The Effect of Extreme Weather Events on Mental Health, National Library of Medicine.

Health Care Pollution And Public Health Damage In The United States: An Update

Sidebar: “UW-Health Sustainability Success Stories”

UW Health Joins Better Climate Challenge, kickstarts new sustainability initiatives

Sustainable Anesthesiology (UW School of Medicine and Public Health)